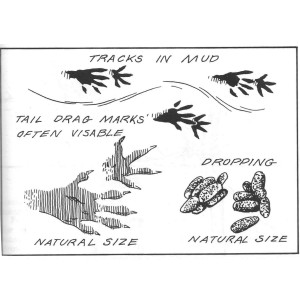

River Otter Restoration

Successful in AK, MO, TN, KY, IL, IN, NC, IA, WV, NE, NY, OH, PA, CO, MD, AZ, MN, OK & KS

Modern foothold traps (these are the same traps used by public trappers) have been used to successfully capture river otter and release them unharmed into other areas of the United States to restore otter populations.